Looking through a file folder named “Cars & Bikes” on my computer the other day, I noticed that in 50 years of riding, I’ve experienced nearly the entirety of motorcycle history. From 1915 Indian board-track racers to a 2022 KTM 1290 Super Duke R Evo, that’s 108 model years’ worth. And in between were tests, rides, or races on more machines from every decade. Hardly planned, this all resulted from simply loving to ride, being curious, and, most of all, saying yes at every chance. Here are some of my favorite moto memories, one apiece covering 12 decades.

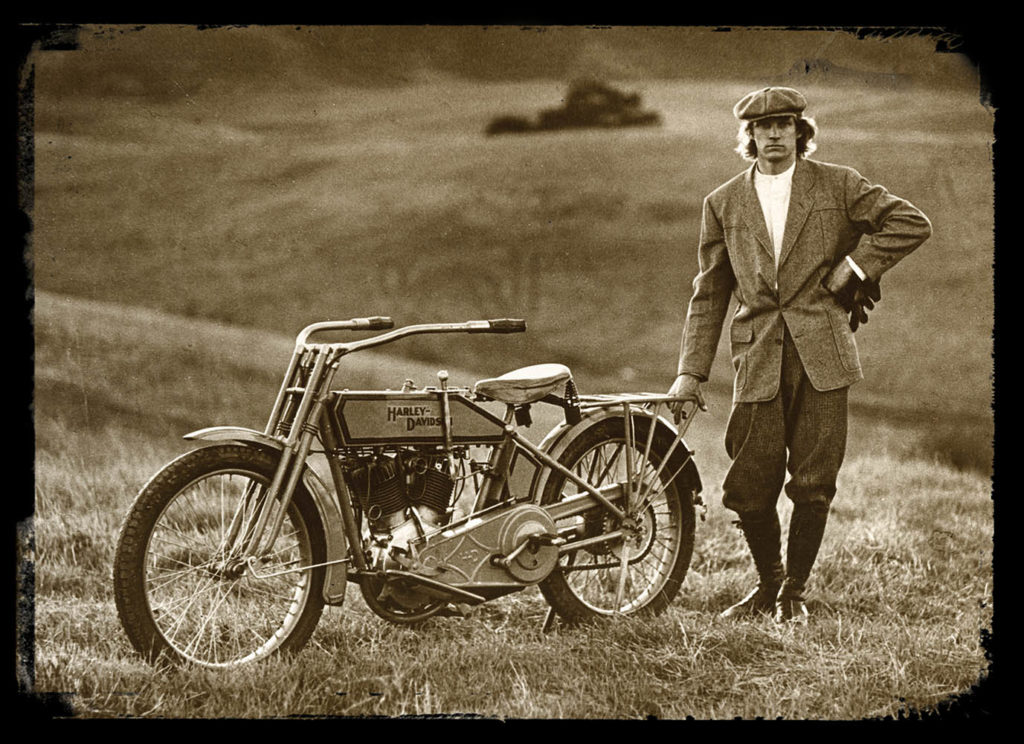

1915 Harley-Davidson Model 11-F

In 1978, Cycle magazine gave me an assignment after I joined the staff: Write a feature about anything I wanted. Interested in the history of our sport, I replied that I’d like to ride a really old bike. “Call this guy,” the editor said, handing me the number of Bud Ekins, an ISDT gold medalist and the stuntman in the epic The Great Escape jump scene.

In his enormous shop, Ekins reviewed the starting drill for his 1915 Harley-Davidson Model 11-F: Flood the carb, set the timing and compression release, crack the throttle, and then swing the bicycle-style pedals hard to get the V-Twin’s big crankshaft spinning. When it lit off, working the throttle, foot clutch, and tank-mounted shifter – and steering via the long tiller handlebar – were foreign to a rider used to contemporary bikes. But coordination gradually built, and after making our way to the old Grapevine north of Los Angeles, I found the 998cc engine willing and friendly, with lots of flywheel effect and ample low-rpm torque to accelerate the machine to a satisfying cruising speed of about 45 mph. And its rider to another time and place.

RELATED: Early American Motorcycles at SFO Museum

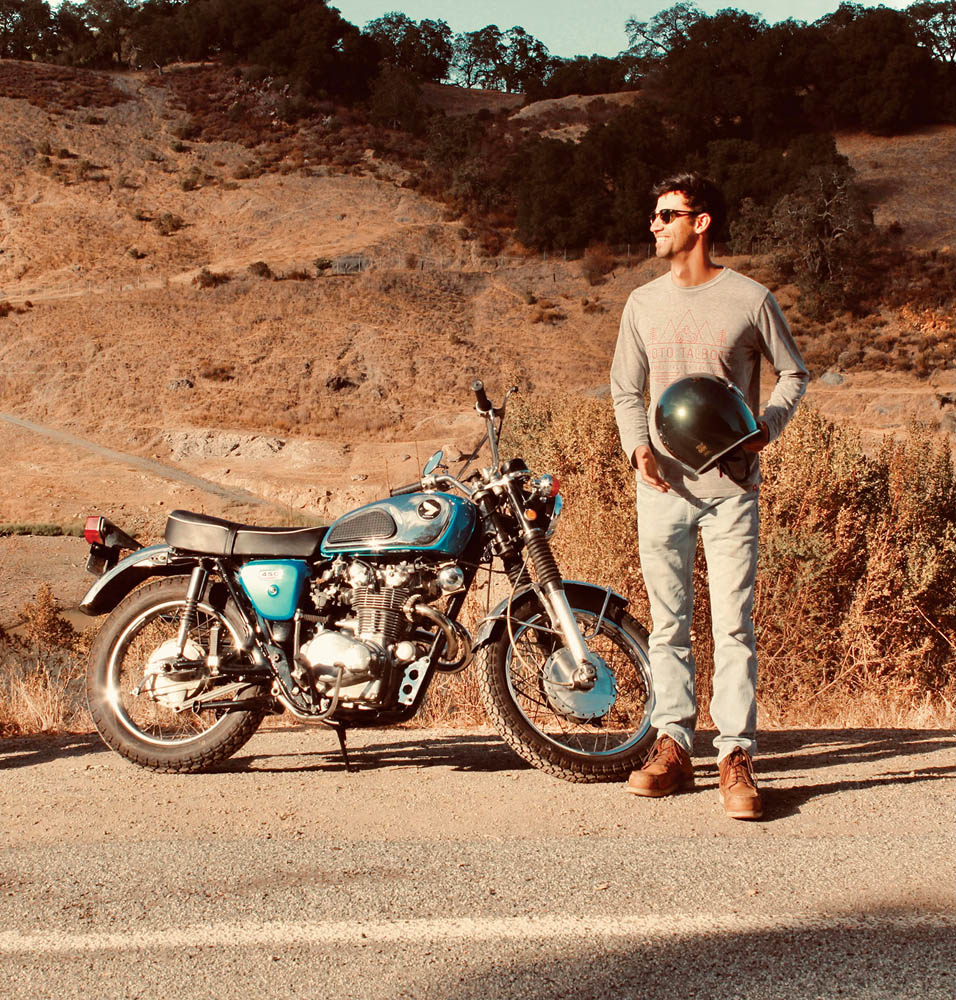

1927 Norton Model 18 TT Replica

On a lucky trip to New Zealand, McIntosh Racing founder Ken McIntosh let me race his special Norton Model 18 in the Pukekohe Classic Festival. Unlike the exotic Norton CS1 overhead-camshaft model that likewise debuted in 1927 – a big advancement at the time – the Model 18 TT Replica used a tuned version of the company’s existing 490cc pushrod Single engine. Its name was derived, fittingly, from the sterling Model 18 racebike’s multiple Isle of Man TT wins. As such, the production TT Replica had as much racing provenance as you could buy at the time.

I found it surprisingly capable, delivering a blend of strong power (a digital bicycle speedometer showed a top track speed of80 mph) and predictable, confident handling – despite the girder-style fork and hardtail frame. However, lacking gear stops in its selector mechanism, the 3-speed gearbox required careful indexing to catch the correct gear. But once I got the process down, the bike was steady, swift, and utterly magical, like the Millennium Falcon of Singles in its time.

RELATED: Retrospective: 1974 Norton Commando 850 John Player Replica

1936 Nimbus Type C

When a friend handed me his 4-cylinder Nimbus, it had big problems. The engine was locked solid, and my buddy wanted to get it running and saleable. Built in Denmark, the Nimbus is unique for several reasons. One is its 746cc inline-Four engine. Rather than being mounted transversely like modern multis, it was positioned longitudinally in the frame, with power flowing rearward via shaft drive. Interestingly, the rocker-arm ends and valve stems were exposed and, when the engine was running, danced a jig like eight jolly leprechauns. The frame was equally curious, comprised of flat steel bars instead of tubing, and riveted together. With a hacksaw, hammer, and some steel, you could practically duplicate a Nimbus frame under the apple tree on a Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday.

Anyway, the seized engine refused to budge – until I attempted a fabled fix by pouring boiling olive oil through the spark-plug holes to expand the cylinder walls and free up the rings. Additionally, I judiciously added heat from a propane torch to the iron block. Eventually, the engine unstuck and, with tuning, ran well. But the infusion of olive oil created a hot mist that emanated from the exposed valvetrain, covering my gear and leaving behind an olfactory wake like baking Italian bread.

1949 Vincent Black Shadow

One blissful time, years before Black Shadows cost six figures, I was lucky enough to ride one. Seemingly all engine, the Black Shadow was long and low, with its black stove-enamel cases glistening menacingly, and its sweeping exhaust headers adding a sensual element to an otherwise purely mechanical look.

Thanks to the big, heavy flywheels and twin 499cc cylinders, starting the Vincent took forethought and commitment. And once the beast was running, so did riding it. A rude surprise came as I selected 1st gear and slipped the clutch near the busy Los Angeles International Airport. Unexpectedly, the clutch grabbed hard, sending the Shadow lurching ahead. The rest of the controls seemed heavy and slow compared to the Japanese and Italian bikes I knew at the time – especially the dual front brakes. The bike was clearly fast, but glancing at the famous 150-mph speedometer, I was chagrined to find that I’d only scratched the surface of the Black Shadow’s performance at 38 mph.

1955 Matchless G80CS

Despite not being a Brit-bike fan in particular, I’ve owned five Matchlesses, including three G80CSs. Known as a “competition scrambler,” in reality the CS denotes it as a “competition” (scrambles) version of the “sprung” (rear-suspension equipped) streetbike. Power comes from a 498cc long-stroke 4-stroke pushrod Single of the approximate dimensions of a giant garden gnome. Starting a G80CS requires knowing “the drill” – retarding the ignition, pushing the big piston to top-dead-center on compression, and giving the kickstart lever a strong, smooth kick all the way through. This gets the crank turning some 540 degrees before the piston begins the compression stroke again.

Once going, the engine fires the G80CS down the road with unhurried explosions. Then at 50 mph or so, the Matchless feels delightfully relaxed; vibration is low-frequency and quite tolerable, and the note emanating from the muffler is a pleasant bark –powerful but not threatening. It is here, at speeds just right for country roads, that the G80CS feels most in its element as a friendly, agreeable companion. With such a steady countenance, it’s no wonder that G80CS engines powered tons of desert sleds. I just wouldn’t want to be stuck in a sand wash on a 100-degree day with one that required more than three kicks to start.

RELATED: Retrospective: 1958-1966 Matchless G12/CS/CSR 650

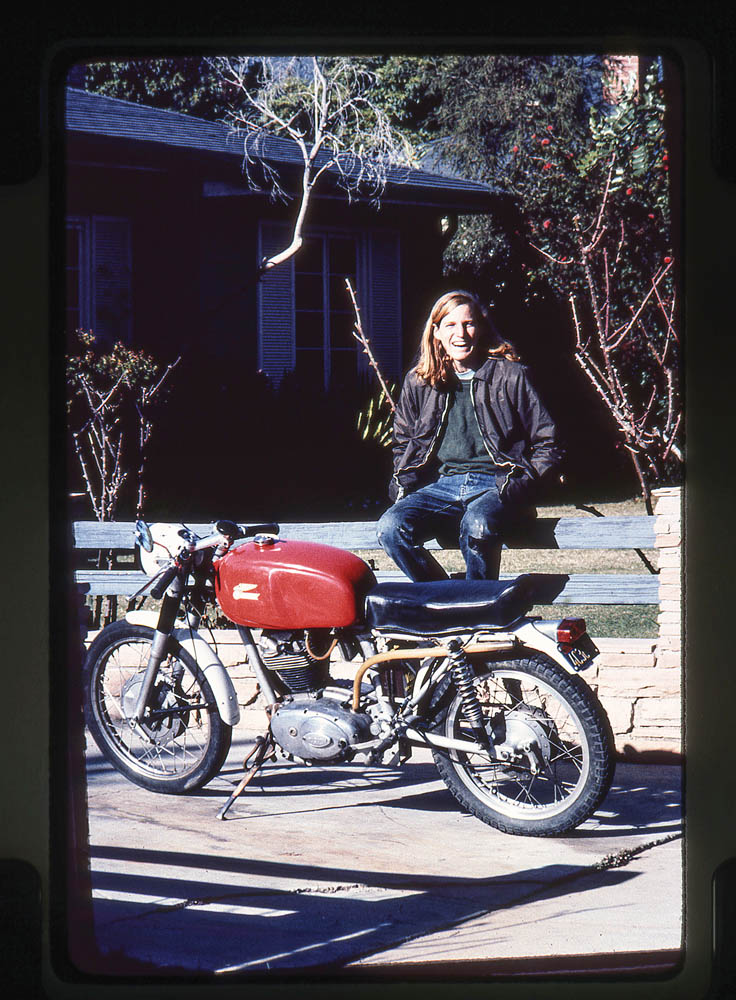

1961 Ducati Diana 250

During Ducati’s infancy, the Italian firm concocted a249cc overhead-cam roadster named the Diana. Featuring a precision-built unit-construction engine like Japanese bikes, it offered an essential difference: being Italian. And that meant all sorts of wonderful learning, as I discovered when, as a teen, I bought a “basket-case” Diana. The term isn’t used much anymore, but it means something has been disassembled so thoroughly that its parts can be literally dumped into a basket. In the case of this poor ex-racer, literally everything that could be unscrewed or pried apart was. The engine was in pieces, the wheels were unspoked, the frame and fork were separated, and many parts were missing.

Its distress repelled my friends but inspired me. Upon acquiring it, a year of trial-and-error work included rebuilding the scattered engine, designing and welding brackets onto the frame for a centerstand and footpegs, assembling the steering, fabricating a wiring harness, and ultimately tuning and sorting. This basket-case Ducati literally taught me the fundamentals of motorcycle mechanics, by necessity. And due to the racy rear-set controls I’d crafted, the machine had no kickstarter, necessitating bump-starting everywhere, every time.

The bike was never gloriously fast, but it carried me through my first roadrace at the Ontario Motor Speedway. After selling it, I never saw it again. Rest in peace, fair Diana. And by the way, the California blue plate was 4C3670. Write if you’ve seen it!

1971 Kawasaki Mach III

Stepping from an 8-hp Honda 90 onto a friend’s Mach III, which was rated at 60 hp when new, was the biggest shock of my young motorcycling life. I knew enough to be careful, not only because of the 410-lb heft of the Kawasaki compared to the Honda’s feathery 202 lb, but because the Mach III had a reputation as a barn-burner. It was true. Turning the throttle grip induced the moaning wail from three dramatic 2-stroke cylinders, and propelled the Kawasaki ahead with a ferocity I’d never come close to feeling before.

In those first moments of augmented g-forces, I distinctly felt that the acceleration was trying to dislocate my hips. In reality, it was probably just taxing the gluteus muscles. But regardless, I remember thinking, “I’ll never be able to ride one of these.” That clearly wasn’t true, but the memory of the Mach III’s savage acceleration and whooping sound remains indelible. Additionally, the engine vibration was incessant – there was simply no escaping it – and in those pre-hydraulic disc days for Kawasaki, the drum brakes seemed heavy and reluctant, even to a big-bike novice. Glad I found out early that the Mach III’s mad-dog reputation was real.

1985 KTM 500 MXC

If Paul Bunyan designed a motorcycle, this KTM 2-stroke would be it. For its day, the 500 MXC was extraordinary at everything, such as extraordinarily hard to start; the kickstart shaft was a mile high and the lever arm even higher. At over6 feet tall in MX boots, I still needed a curb, boulder, or log handy to effectively use the left-side kickstarter. The motor had so much compression (12.0:1) that this Austrian Ditch Witch practically needed a starter engine to fire the main one. Once, I was stuck on a desert trail with the MXC’s engine reluctant to re-fire. Not so brilliantly, I attached a tow line to my friend’s Kawasaki KX250 and he pulled me to perhaps 25 mph on a nearby two-lane road. Before I could release the line and drop the clutch, my buddy slowed for unknown reasons. Instantly the rope drooped, caught on the KTM’s front knobby, and locked the wheel, slamming the bike and its idiot rider onto the asphalt. The crash should have broken my wrist, but an afternoon spent icing it in the cooler put things right.

When running, though, the MXC was spectacular. Capable of interstate speeds down sand washes and across open terrain, the liquid-cooled 485cc engine was a maniacal off-road overlord. The suspension included a WP inverted fork and linked monoshock with an insane 13.5 inches of travel out back. I bought the 500 MXC used for $500, and I had to practically give it away later. But now, I wish I had kept it, because it was fully street-plated – ideal for Grom hunting in the hills today.

1998 Yamaha YZF-R1

On a deserted, bucolic section of Pacific coastal backroads, I loosened the new Yamaha R1’s reins, kicked it in the ribs, and let it gallop. And gallop it did, at a breathtaking rate up to and beyond 130 mph. That’s not all that fast in the overall world of high performance, but on a little two-lane road edged by prickly cattle fences and thick oaks, it ignited all my senses. What had been a mild-mannered tomcat moments before turned into a marlin on meth, but it wasn’t the velocity that was alarming.

No, the point seared into my amygdala was how hard the R1 was still accelerating at 130 mph. Rocketing past this speed with a ratio or two still remaining in the 6-speed gearbox sounded every alarm bell in my head, so I backed down. Simply, the R1 rearranged my understanding of performance. But simultaneously, it made every superbike of the 1970s, including the King Kong 1973 Kawasaki Z1 – the elite on the street in its era – seem lame by comparison.

2008 Yamaha YZ250F

After 25 years away from motocross, in 2008 I bought a new YZ250F and went to the track. Oh, my word. The dream bikes of my competitive youth – Huskys, Maicos, Ossas, and their ilk – faded to complete irrelevance after one lap at Pala Raceway on the modern 4-stroke. Naturally it was light, fast, and responsive, but the party drug was its fully tunable suspension. By comparison, everything else I’d ridden in the dirt seemed like a pogo stick. Together, the awesome suspension and aluminum perimeter frame turned motocross into an entirely different sport, and I loved it anew.

In retrospect, the glorious old MX bikes were dodgy because real skill was required to keep them from bucking their riders into the ditch. But, surprisingly, I found motocross aboard this new machine still merited hazard pay, for two reasons: 1) Thanks to the bike’s excellent manners, I found myself going much faster; and 2) Tracks had evolved to include lots of jumps, sometimes big ones. Doubles, step-ups, table-tops – I later paced one off at Milestone MX and realized the YZ was soaring more than 70 feet through the air.

2017 Yamaha TW200

There’s something about flying low and slow that’s just innately fun. Just ask the Super Cub pilots, lowrider guys, or Honda Monkey owners. After a day in the Mojave, plowing through sand, sliding on dry lake beds, and dodging rocks and creosote bushes, Yamaha’s TW200 proved equally enamoring. Yes, it’s molasses-slow, inhaling hard through the airbox for enough oxygen to power it along. And it’s built to a price, with an old-school carburetor and middling suspension and brakes.

Nonetheless, its fat, high-profile tires somehow make it way more than alright, kind of like riding a marshmallow soaked in Red Bull. Curbs? Loading docks? Roots, ruts, and bumps? Scarcely matters at 16 mph when you’re laughing your head off. Top speed noted that day was a bit over 70 mph – good enough for freeway work, but just barely. So, actually, no. But throttling the TW all over the desert and on city streets reminded me just how joyous being on two wheels is.

RELATED: Small Bikes Rule! Honda CRF250L Rally, Suzuki GSX250R and Yamaha TW200 Reviews

2020 Kawasaki Z H2

Building from its supercharged Ninja H2 hyperbike, Kawasaki launched the naked Z H2 for 2020. Lucky to attend the press launch for the bike that year, I got to experience this 197-hp missile on a road course, freeways, backroads, and even a banked NASCAR oval. The latter was, despite its daunting concrete walls, an apropos vessel to exploit the bike’s reported power. Weighing 527 lbs wet, the Z H2 has a 2.7:1 power-to-weight ratio – nearly twice as potent as the 2023 Corvette Z06.

Supercharged engines are known for their low-end grunt, and the Z H2 motor was happy to pull at any rpm and in any gear. But it fully awakened above 8,000 rpm, as the aerospace-grade supercharger began delivering useful boost. From here on, the job description read: Hang on and steer. Free to pin it on the road course and oval, I did. And not for bravado’s sake – I really wanted to discover the payoff of having so much power. As it turns out, a supercharged liter bike dramatically shrinks time and space, making it a total blast on the track – and absolute overkill on the road. Watch where you aim this one.

Based in Southern California, John L. Stein is an internationally known automotive and motorcycle journalist. He was a charter editor of Automobile Magazine, Road Test Editor at Cycle, and served as the Editor of Corvette Quarterly. He has written for Autoweek, Car and Driver, Motor Trend, Cycle World, Motorcyclist, Outside, and other publications in the U.S. and abroad.

The post Riding the Motorcycle Century first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com