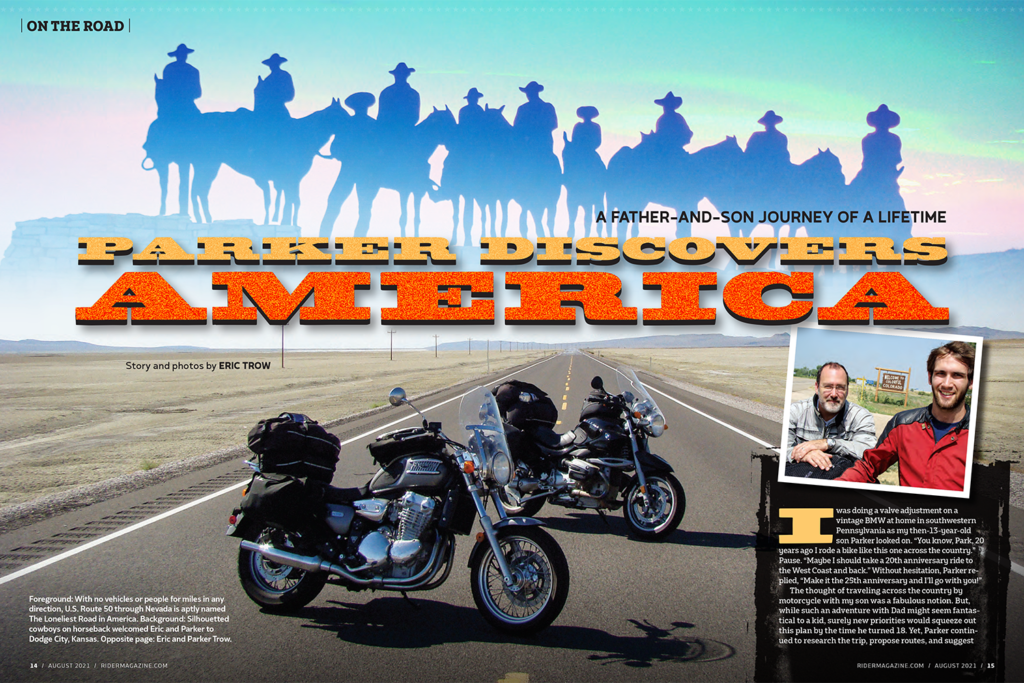

No more than 10 miles from where I learned to ride a motorcycle is one of our country’s finest set of twists and turns. Prejudiced, you may be thinking, but these are not just my thoughts. They come straight from Car and Driver magazine, which in 2020 published a list of the dozen best driving (and riding!) roads in America. First on their list: Ohio State Route 555, also known as the Triple Nickel.

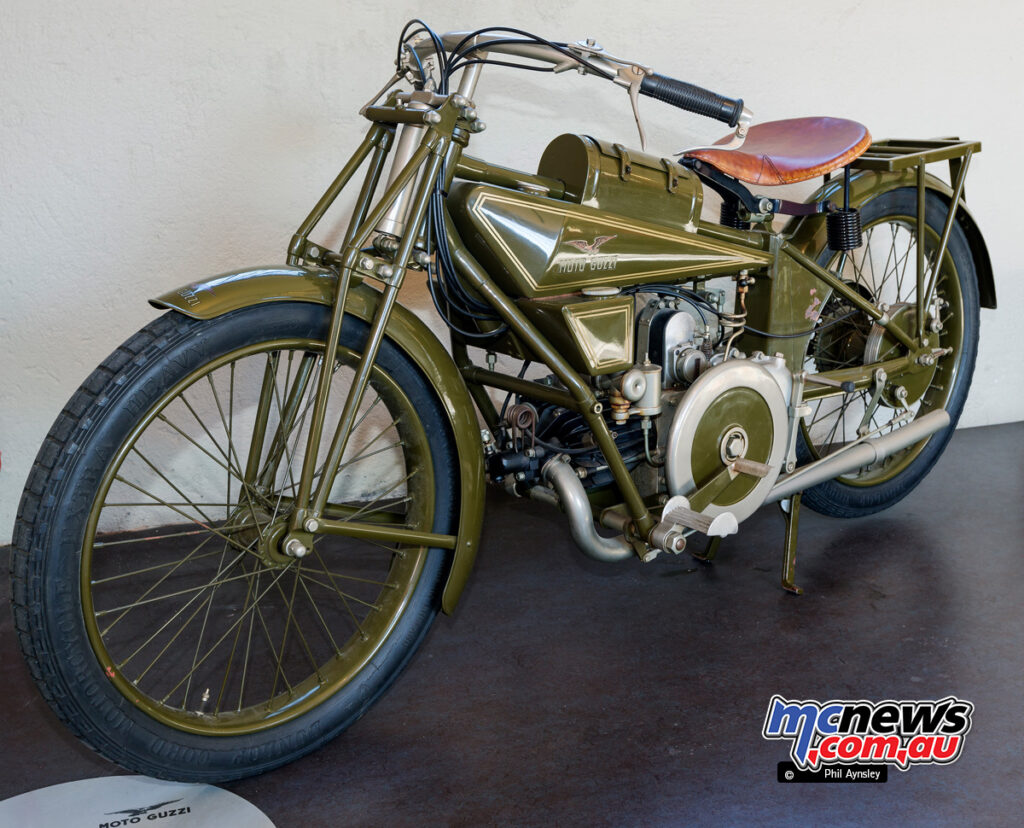

It’s a throwback, a two-lane highway built in another era, originally a gravel road for farmers and small-town folk to get to the big cities of Zanesville or Belpre, back in the Depression years when you might find a Hudson or Studebaker puttering along its 63 miles, the driver cursing every twist and turn that today make it a destination for car and motorcycle enthusiasts.

Nicholas Wallace introduced his Car and Driver piece by writing about the mystique of the best places to aim your car, or in our case, motorcycle: “Looking for an adventure – even if only in your mind? Let these treks take you away. Maybe it’s the fact that, despite constricting responsibilities and busy schedules, the car still stands as a beacon of freedom in our daily lives. It would take us hundreds of pages to list every great road, so instead we’ve brought you twelve of the best. Twisty, scenic, dangerous, and remote, these routes offer a lifetime’s supply of variety. So pack your stuff and head out – we promise it will be worth it.”

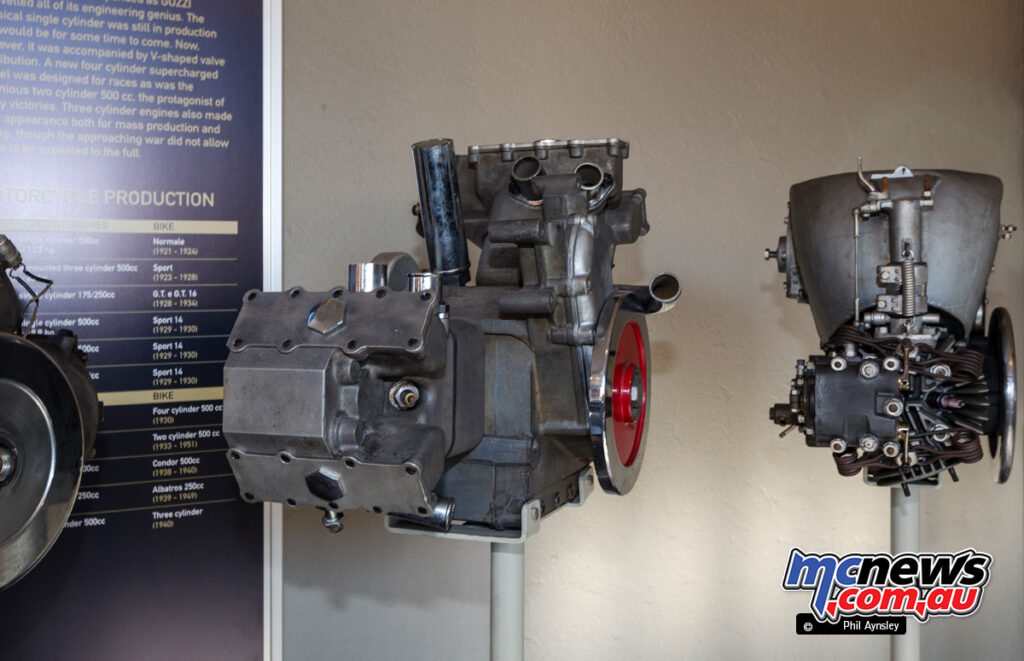

Our motorcycles offer us that same beacon of freedom. Starting just south of Zanesville, I’ve been down our great Ohio highway many times, always on something made for scraping footpegs, not that I still have that kind of nerve. But today was to be different. For this ride I’d be on three wheels, on my brother’s Can-Am Spyder. It was to be my maiden voyage, my first time on his trike, soon to be mine. Chuck had warned me about an adjustment period, the time it would take to get comfortable on a machine so different from the two-wheeled motorcycles that have carried me for over half a million miles.

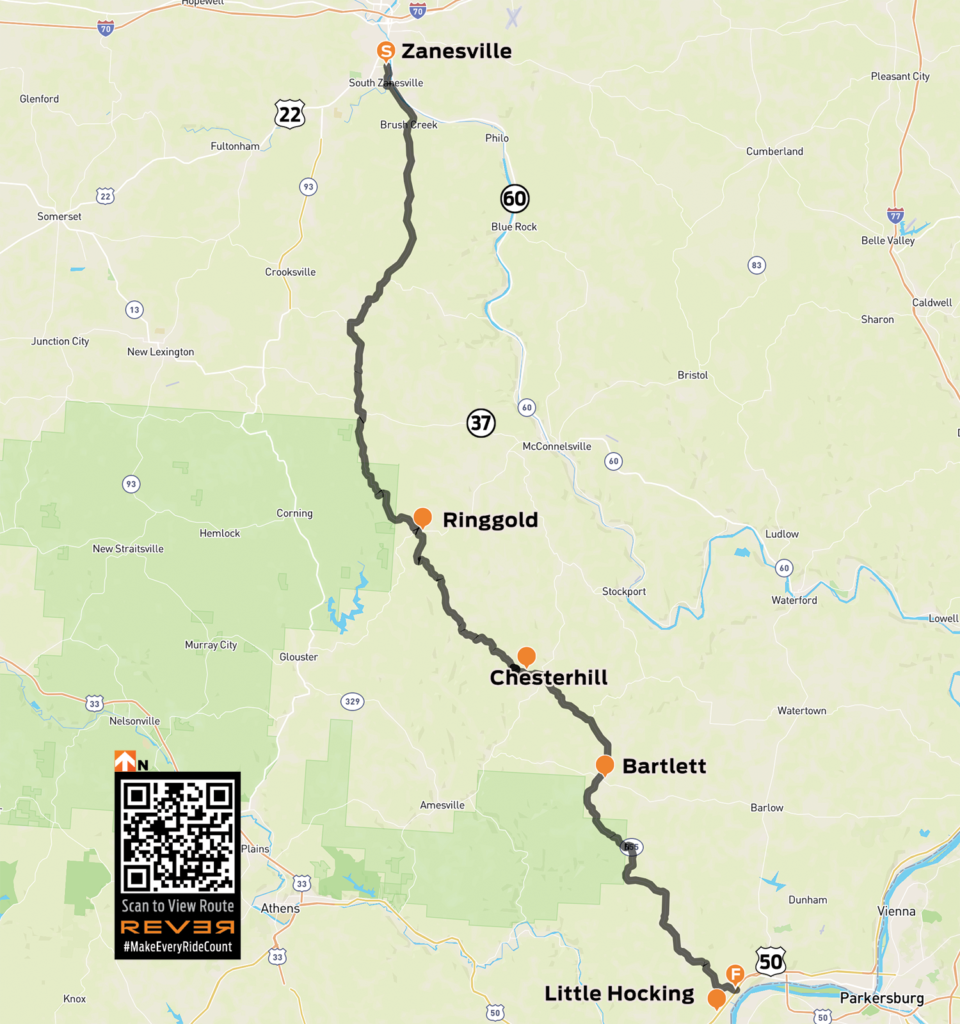

Click here to view/download the Triple Nickel route on REVER

But my life had changed. Two vertigo attacks within three days had forced me to open my eyes to what might come next. The first bout had been when riding my Beemer on a western Ohio county road. In an instant I simply lost all sense of balance, going left of center and crashing in a farmer’s front yard. Luckily, I was unhurt and there was little damage to my bike. The second attack, when in my car, sealed the deal. For nearly a year since my crash, I’d been without a bike, until today.

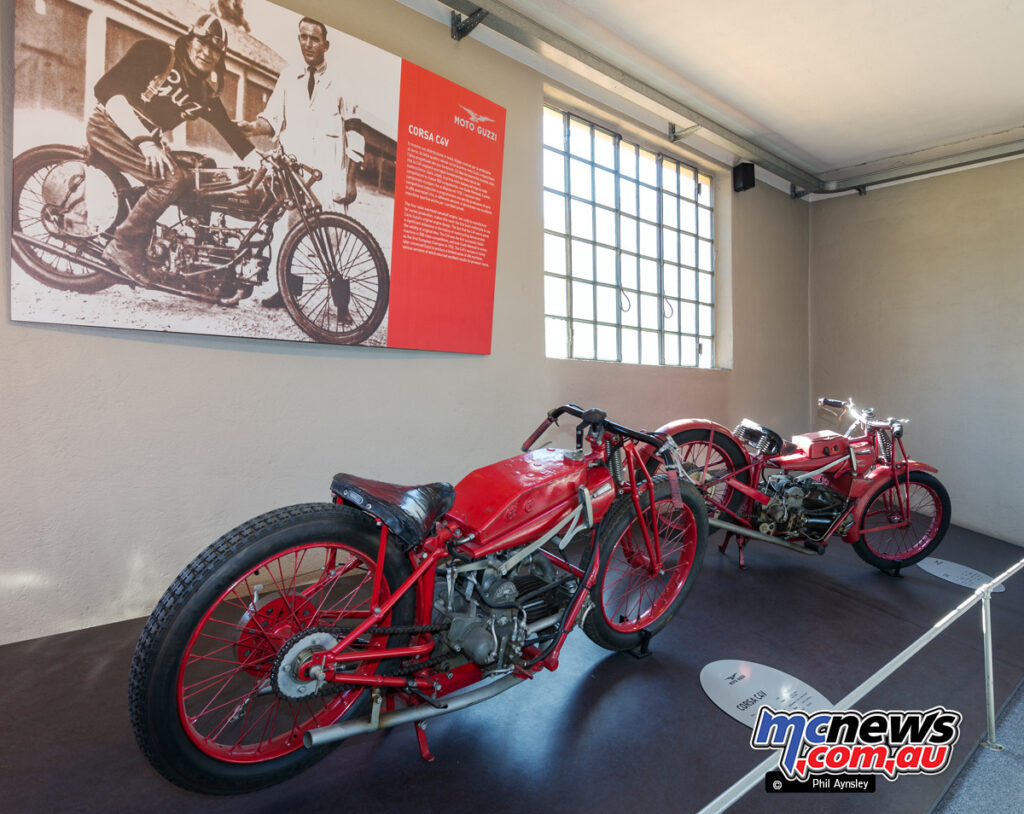

The three-wheeled cycle, a 2014 model, had been Chuck’s pride and joy, the best bike he’d ever owned, he told me. Riding it that day was bittersweet. It should have been Chuck out on his Spyder. But his life had taken a turn of its own. For half of his 66 years he’d been plagued with muscular dystrophy, the disease slowly eating away at his ability to get around. It had finally gotten the upper hand, relegating Chuck to a walker and a wheelchair.

But he had not gone quietly into his new solitude. Over the previous several years, Chuck had a single focus: to get his Spyder to 200,000 miles. He’d pushed hard, riding hundreds of miles every day. Only three years earlier he’d ridden over 43,000 miles in 12 months, with every year but the last tallying well over 30,000. But last June, at the height of the riding season, his body told him it was finished. It was done. (You can read more about Chuck’s high-mileage pursuits in “Chuck’s Race”.)

Chuck had put up a valiant fight, but there are some things a human being simply can’t overcome. That last day, when he parked his trike, its odometer was frozen at 188,303 miles. But now, on this day – my day – it was to move again. It had fresh oil and a full tank of gas, so all I had to do was to check the tire pressure. Chuck had kept his Can-Am road-ready all winter, sometimes visiting and sipping a beer or two, reminiscing about the good old days, sometimes firing it up, simply to listen to the Spyder’s engine quietly humming along.

The Spyder had been waiting, patiently, for nearly a year for its next adventure. It had waited long enough. Me too! For his trike, this was to be a new spring with a long summer ahead. There were miles to be ridden, new places to explore, with me holding the grips.

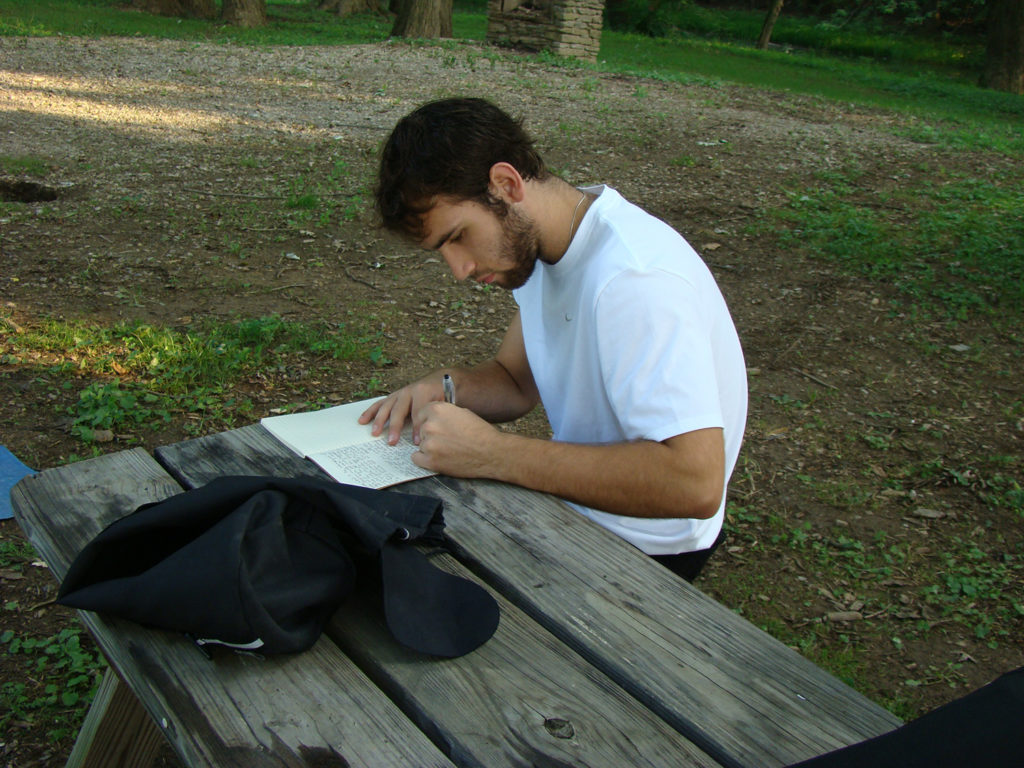

It was to be a careful ride. It was me that had to be broken in. Chuck watched as I rode up and down his rural road, getting my first feel of the Spyder. I couldn’t help but wonder what was going through his mind. He knew it would be my goal to get his Spyder’s odometer in motion once again, to get it past 200,000 miles. His trike was not meant to sit as a quiet monument to its past glory. What Chuck knew, in no uncertain terms, was that the road was where his Spyder was meant to be. And maybe, hopefully, this year it would take me along other top-ranked riding roads.

With both Chuck’s and my limitations, this three-wheeled cycle was meant for where I was heading. True, on a road meant for many to be a test of their riding talents, maybe riding the Triple Nickel wasn’t my wisest decision. There would be a learning curve, that I knew. But what better road was there to get the feel for the Spyder, to accelerate that learning curve, than where others went to challenge themselves. And for my Sunday ride, this highway, one of Ohio’s least traveled, was perfect.

“While not the most technical course,” Wallace wrote, “the Triple Nickel’s combination of high-speed sweepers and tight, low-speed corners means there’s something for everyone.” Granted, the other 11 highways in his story may have offered something more unique, a view of the Pacific, or the northern tundra along the Top of the World Highway, or the relentless craziness of the Tail of the Dragon. Of the nine highways on the list I’d ridden, the Triple Nickel, with its twists and turns, may have more closely resembled Mulholland Drive in California. But as I rode on, there was no question that Ohio State Route 555 fit right in.

This ride offered me the solitude I needed. This was a reawakening for me, a bridge from my past to a new future, to again feel the wind and see the road surface blurring beneath me. But respect for the highway was in order. The riding rules had changed. The undulating highway surface beneath me, not my natural sense of balance when on two wheels, set all of the rules. There was an initial element of uncertainty, with me in an unsettled place, somewhere between riding on two wheels and driving a car.

At one of my stops, local resident Tom Collins, who had seen me ride by and knew of this highway’s history all too well, summed up its danger in only one sentence, reminding me that, “For every mile of highway, there are two miles of ditches.” Riding buddy Mac Swinford added, “The 555, especially between Ringgold and Chesterhill, resembles a paved footpath constructed by a drunk who hated people.”

Cannelville, then Deavertown and Portersville, were first in line, three tiny towns forgotten as soon as I rode beyond them, reminded of their names only by looking at my map. Then Chesterhill, a quaint and attractive community, and Bartlett, where you can find lunch if you know where to look. You can get gas just north of Chesterhill on Ohio Route 377, and in Bartlett a half mile to the east on Ohio 550, another great ride by the way, but nowhere else

The highway draws you in, encompassing you in a unique way. Then all too suddenly, once after little Decaturville, then into Fillmore and near Little Hocking, the highway ends. One minute you’re on the highway, and then the next it’s over, finished. There’s not even a sign. Every time I ride this road there’s an immediate sense of disappointment, wishing there was more.

If it hadn’t been for my brother’s Spyder, I doubt I’d ever have ridden again. At 72 years of age, I might have simply allowed myself to leave behind the joy of riding I’ve known from before my adult years. Chuck sensed it too. He wanted me to ride toward a sunset he could no longer enjoy. There are always new highways, singular places we need to find, known and unknown to us. This day I was being introduced to the Spyder that would take me to many of them.

This highway is worthy of its #1 ranking, with its endless array of ups and downs and arounds, where not long ago I might have stretched my limits. But that was not my purpose this first day on the Spyder. By the end of my ride, I knew Chuck’s trike a lot better. I knew after the Triple Nickel’s 63 miles it was something I could get used to. I should know better by the time the odometer rolls over 200,000 miles.

Ride on!

The post Riding Ohio’s Triple Nickel first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com