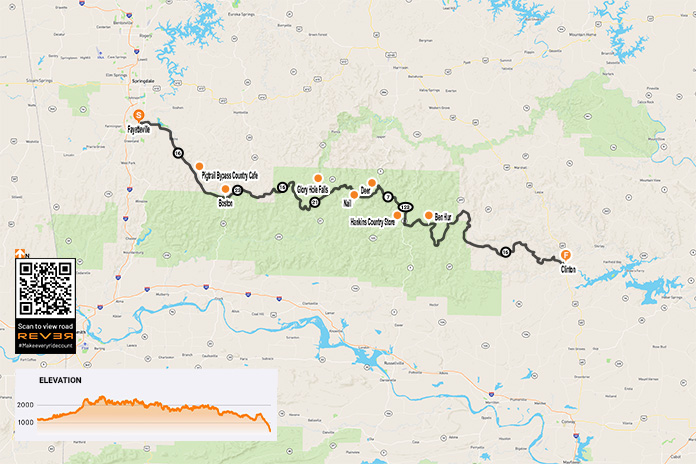

If you’re planning a motorcycle tour in Eastern Oklahoma and you want to find the best roads and the most scenic and historic sites, take a ride with Oklahoma locals Bill and Susan Dragoo in this feature, “Riding the Territory,” from the pages of Rider magazine’s October issue. Scroll down for a route map and a link to the route on REVER.

Red skies silhouette the towering sandstone spires of Monument Valley. A six-horse team gallops across the movie screen in the foreground, pulling a stagecoach trailing a cloud of dust as the occupants desperately try to escape a band of mounted Plains Indians shooting arrows and sending up war whoops. It’s an exciting scene and an image that easily comes to mind when we try to picture life in the 1800s west of the Mississippi. The “Wild West,” in other words.

While that iconic scene may have occurred at some moment in time, a depiction of Western adventure somewhat closer to reality is the story of True Grit, in which aging U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn is recruited by a teenage girl to track down her father’s killer in the dangerous, outlaw-ridden Indian Territory during the days of “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker.

The Indian Territory – what is now Eastern Oklahoma – truly had its share of outlaws in the days after the Civil War. Cattle rustlers, horse thieves, whiskey peddlers, and bandits sought refuge in the untamed territory. For many years, the only court with jurisdiction over white men in Indian Territory was the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas located in Fort Smith, where Judge Parker held the bench for 21 years and handed down 160 death sentences.

Those outlaw days left a colorful legacy still recognizable in places like Horsethief Springs, Robbers Cave State Park, and the Fort Smith National Historic Site. And thanks to its hilly topography, Eastern Oklahoma is not only full of historical riches but also rife with great motorcycle roads. The Ozark Plateau stretches over from Arkansas into northeastern Oklahoma, and farther south, the Ouachita Mountains provide an even craggier landscape. As a result, the roads – once foot trails, wagon roads, stagecoach routes, and military roads – are a playground for motorcyclists.

Scan QR code above or click here to view the route on REVER

Wonderful paved twisties and miles of dirt and gravel backroads pervade the hills and hollows, flowing through this sparsely populated countryside. The feeling is one of remoteness, even if you’re never very far from a stretch of highway that will get you to an outpost of civilization.

We’ve spent much of our lives exploring Oklahoma. And while we live in the prairies farther west, the deep green forests and remote byways of the state’s eastern region keep drawing us back, time after time.

For us, a perfect starting point for a multiday tour of Oklahoma’s “Green Country” is Tahlequah. Situated about 70 miles southeast of Tulsa, Tahlequah is the modern headquarters of the Cherokee Nation and the end point for the Cherokees’ forced removal from their homeland east of the Mississippi. This relocation took place during 1838 and 1839. Other eastern tribes affected by the forced-removal policy of the U.S. government that would later come to be known as the “Trail of Tears” included the Choctaws, Creeks (Muscogees), Seminoles, and Chickasaws. Along with the Cherokees, they were known as the “Five Civilized Tribes.”

For more information about Tahlequah and the surrounding area, visit TourTahlequah.com

Once re-settled in Indian Territory, they rebuilt their societies, governed themselves, and lived in relative peace and prosperity until the devastation of the Civil War, after which white settlers inundated the Territory. Oklahoma statehood in 1907 erased tribal sovereignty. In the 1970s, legislation restored the tribes’ ability to exercise powers of self-government, allowing entities such as the Cherokee Nation to thrive.

Tahlequah’s historic sites require a leisurely day or two to enjoy, so we recommend spending some time there seeing the Cherokee National History Museum, housed in the renovated Cherokee National Capitol. Also in downtown Tahlequah is the Cherokee National Supreme Court Museum, which was built in 1844 and housed the printing press of the Cherokee Advocate, the first newspaper in Oklahoma. This museum is the oldest government building in Oklahoma. Hunter’s Home in nearby Park Hill is the only remaining pre-Civil War plantation home in the state.

When you’re ready to get on the road, cruise north from Tahlequah on State Highway 10 along the Illinois River, one of Oklahoma’s few state-designated scenic rivers and a popular site for floating, fishing, and camping. Stay on Highway 10 or veer off at Combs Bridge, crossing the Illinois River to explore an easy dirt road squeezed between the river and the bluff. It winds through farmland and across an area of cascading water called Bathtub Rocks.

At Combs Bridge, you can also pick up the Green Country Oklahoma Adventure Tour (GOAT), a route of about 500 miles almost entirely within the Cherokee Nation. The GOAT follows public roads with loose gravel, large rocks, mud, steep hills, and an abundance of water crossings, making for a lot of fun, especially after a good rain.

If you’re more into pavement, continue northeast on Highway 10 to U.S. Route 412 and detour to beautiful Natural Falls State Park, which offers a short hike to a 77-foot waterfall and dripping springs. Grab lunch in nearby Siloam Springs, Arkansas, and return west to Highway 10/U.S. Route 59 for a pavement ride north over Lake Eucha to State Highway 20, which takes you on a super-twisty route around Spavinaw Lake southwest to Salina, the oldest European-American settlement in Oklahoma. In 1796, Jean Pierre Chouteau encouraged several thousand Osage people to move from Missouri to what would become northeastern Oklahoma, establishing a trading post at present-day Salina. An old salt kettle in a city park along Highway 20 is all that remains of this rich history.

From Salina, State Highway 82 returns you to Tahlequah, but if you have time, veer west on State Highway 51 and catch State Highway 80 for a jaunt south on a twisty paved road along the eastern shore of Fort Gibson Lake and continue to the Fort Gibson Historic Site.

Built in 1824, this was the first military post established in Indian Territory and was intended to maintain peace between the Osages and Cherokees. It figured prominently in the forced relocations of the 1830s and served as a base for military expeditions exploring the West. It was abandoned in 1857 but reactivated during the Civil War. The army stayed for some years after the war, dealing with outlaws and keeping the peace. Visitors can see a 1930s reconstruction of the early log fort and the stockade, as well as original buildings dating back to the 1840s.

From Fort Gibson, loop back to Highway 82 and ride along the eastern shore of Lake Tenkiller, where Tenkiller State Park offers another good spot for camping, as well as lodging in cabins. Continuing south, a short detour out of Sallisaw brings you to Sequoyah’s Cabin Museum. Sequoyah created a system of writing for the Cherokee people and built this log cabin in 1829. It is enclosed by a stone structure built in 1936.

Just north of Sequoyah’s Cabin is one of the more technical segments of the GOAT, the rough and rocky Old Stagecoach Road. Which stagecoach line used the road is unclear, but it is definitely old. The road shows up clear as day on a 1901 topographic map, following West Cedar Creek through a gap in the Brushy Mountains. With a moderate level of skill, an average rider can negotiate Old Stagecoach Road.

Continuing south takes you into the Choctaw Nation. At Red Oak, catch some twisty pavement over the mountains on Highway 82, ending up in Talihina. Or turn west at Red Oak on State Highway 270 and spend a day at Robbers Cave State Park just north of Wilburton, where Civil War deserters and outlaws – including the Youngers, the Dalton Gang, and Belle Starr – reportedly hid in the park’s namesake cave.

Legend has it that the remote location and rugged terrain made the cave a nearly impregnable fortress, with the criminals able to escape through a secret back exit. We’ve been in the cave, and that “back exit” looks like a tight squeeze and a dead end. The park also features camping, lodging in vintage cabins built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and some of the state’s best hiking.

Heading on toward Talihina, you enter the Ouachita National Forest and some of the most spectacular riding in Oklahoma, on or off pavement. The star of the show in this region is the Talimena Scenic Drive, which begins just northeast of Talihina. The serpentine 54-mile national scenic byway steeply ascends Winding Stair Mountains, staying on the crest as it crosses over into Arkansas. Across the state line atop Rich Mountain, Queen Wilhelmina State Park is a popular stop. At nearly 2,700 feet elevation, Rich Mountain is Arkansas’ second highest peak, and the spot offers breathtaking scenery when the clouds aren’t draped over the mountaintop.

The Talimena Scenic Drive also boasts multiple offshoots for unpaved riding, and hiking trails abound. One popular footpath is Horsethief Springs, which follows a route horse thieves used in the 1800s, making their camps and corrals near the top of the mountain near a perennial spring. A stone structure built by the CCC in the 1930s now surrounds the spring, which had run dry the last time we passed through.

For hardcore hikers, the 223-mile Ouachita National Recreation Trail runs along this same ridge. We’ve backpacked the trail from Talimena State Park to Little Rock, Arkansas, in a series of section hikes and can affirm that steep, difficult climbing does not require high elevations. Nearby you can also pick up the Oklahoma Adventure Trail for more off-road two-wheeled exploration. This approximately 1,500-mile mostly unpaved trail circumnavigates Oklahoma and offers a huge variety of terrain.

The Talimena Scenic Drive drops you off in Mena, Arkansas, and from there you can follow U.S. Highway 71 to Fort Smith. The Fort Smith National Historic Site and its surroundings offer a glimpse into a spot that was once the westernmost military post in the United States and later became best known for the justice meted out by Judge Parker. A reproduction of the gallows and Parker’s restored courtroom are among the exhibits.

From Fort Smith, take a leisurely ride north on Arkansas Highway 59, a scenic paved road hugging the border between Oklahoma and Arkansas. Along the way, make a stop at Natural Dam Falls, a lovely waterfall just off the highway. Near Dutch Mills, Arkansas, take a short side trip to Cane Hill, where you’ll swear you just emerged from a time warp. Attracted by the area’s natural springs, Cane Hill’s first European settlers established a township there in 1829. A museum and walking trails help the visitor interpret and explore the community’s well-preserved historic sites.

Jog back to Highway 59 northbound to U.S. Highway 62, which crosses into Oklahoma at Westville, the easternmost point of the Trans-America Trail as it begins its Oklahoma segment across the state’s northern tier.

Back in Tahlequah, pick up where you left off with historical exploration, or take a break and float the Illinois. No matter what you choose, take a moment to contemplate the Western history you’ve just experienced. Then go watch True Grit again.

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Rider.

The post The Best Motorcycle Ride in Eastern Oklahoma first appeared on Rider Magazine.

Source: RiderMagazine.com